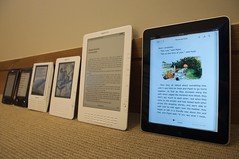

John Blyberg via Compfight

John Blyberg via CompfightThe other day I was listening to a Planet Money podcast episode, and they were talking about a new-to-me financial term: the discount rate. As they described it, this is “the rate you use to size up future costs.”

This morning I read a blog/essay by cartoonist Dave Kellett (who draws the nerdy-fun comic Sheldon) which argued that ebooks in libraries would be the death of the traditional publishing industry. As he put it, “The internet has shown, again and again, that the average consumer always tends toward the cheaper, faster solution. And all things being equal between delivery systems, there’s no debate which one is more advantageous for the individual: The borrowed copy.”

Not long after reading this essay, I attended a training session by one of our ebook vendors, during which at one point they mentioned that the cost for MUPO books (multiple simultaneous user access; essentially a site-license) as being only 150% of list price, which in their words is a good deal. I held my breath for a moment, as I knew the cost of MUPO had been contentious in internal discussions in the recent past. However, the moment passed without comment.

All of these bits and pieces began churning in my mind until finally I reached a rather shocking to me conclusion: 150% of list price for unlimited simultaneous user access is an amazing deal, particularly now that these ebooks are becoming more functional for the users.

Think about it — for the cost of half of a second copy, any number of our users can view, download, print, copy, and even read the same book at the same time. In the print world, at best you might get four people reading the same copy a book at the same time if you could smoosh together close enough and the font size wasn’t too small. Or, you’d buy multiple copies for class reading assignments that would then end up being discarded when the curriculum changed.

How could I go from thinking that ebooks shouldn’t cost more than print to thinking that MUPO pricing is a good deal? Well, my discount rate changed. When I thought about it from the perspective of copies saved rather than prices increased, it made the cost difference seem less heinous.