Last year was a strange year for music in my life. January and February passed much as they had for years before, with most of my music listening being done in service of my show on WRIR. I had decided in late January that I wanted to step back from doing a weekly show, but it took another month for the program director to find hosts to replace me. As it happened, I stopped doing my show just one week before the realities of COVID hit and Virginia went into a state of emergency.

I began working from home, and found that the quiet, intermittently interrupted by noises from my neighbors on either side of my townhouse, was not easy to stay focused in. I needed something to listen to. But what?

For a while, I would tune into WRIR and have the news and public affairs programming that ran from 8am to 3pm most weekdays fill that space, but some of it was annoying to me, and I’d shut that off. I tried listening to some albums on Spotify, or playing some Spotify playlists, but after a while, that got annoying, too.

When it became clear that this wasn’t going to be a short-term arrangement, I reworked my home office to accommodate my work equipment (laptop, keyboard, mouse, and dual monitors). To do this, I turned my chest of drawers into a stand-up desk for my home computer, and moved my work setup from the dining table up to my desk, which is also in my bedroom. Aside from wanting a more functional workspace, this gave me back my table and put me within range of my 87GB digital music library, with nearly 13,000 songs.

For most of the 2000s and the early part of the 2010s, I spent a lot of time and money collecting CDs of anything I thought I might enjoy. More than I made time to listen to. But now I could work and listen to as much of it as I wanted, and so I did.

Back in 2010, when Lifehacker was actually useful, I read an article about how to make a few smart playlists that would ultimately create a playlist that would shuffle through your entire music collection, hitting up favorites more frequently, and ensuring that at some point, you’d hear every track. I had made such a playlist then, throwing a random 6 hours of it onto my iPod to take with me to work. But, it was kind of a hassle, and after a few years I stopped doing it at all. TBH, I’m not sure where I put my iPod after I finally bought an iPhone.

Months have passed since I moved up to my bedroom, and during that time, I listened to a lot of music from my personal digital library (and some still from Spotify, as well as a few favorite WRIR shows). I also paid for a Last.fm account, because I wanted the report function. And now that the year is over, I’m eager to reflect up on the data.

One thing that stands out is that Enya was the top artist, her album Watermark was the top album, and the top track was the song “Watermark”. I do love me some Enya, but those stats mainly came from a period of time prior to the move closer to my music library, and early in the pandemic when I was reaching for anything to calm and comfort me. Watermark is still a fantastic album, and I do not begrudge it the top spot.

The other thing that stands out is how much listening to only my small collection of Christmas albums in December really skewed the album chart. Half of the top 20 albums for the year were Christmas albums.

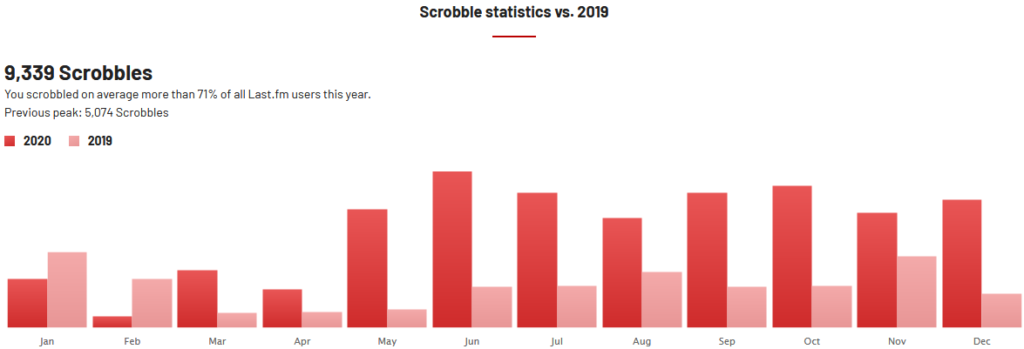

You can definitely see the change in my music listening habits prior to the pandemic (Jan-Feb), the early months of the pandemic (Mar-Apr), and when I moved to my current home office space in May.

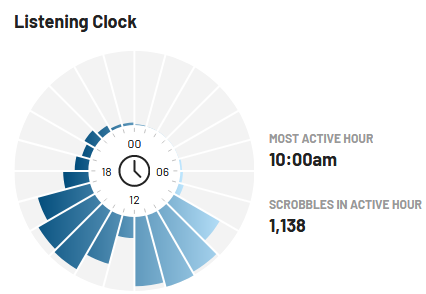

I mostly listen during the work day, with some evening jamming.

Because I wasn’t listening to as much fresh-off-the-presses music as I had done in previous years, I dropped a few spots on the discovery leaderboard. On the flip side, my personal collection is apparently less mainstream than the music I was listening to in 2019 that had been sent to a non-commercial community radio station. Go figure.

I checked my iTunes library, and I still have another thousand or so songs to listen to for the first time (in iTunes – many I had heard elsewhere which prompted the acquisition of my own copy). I am hoping that by this time next year, that number will be much smaller.

Finally, I will leave you with what I consider to be the song of 2020. At least for anyone who listens to Reply All.