Speaker: Daryl Yang

Why collaborate?

Despite how popular Apple products are today, they almost went bankrupt in the 90s. Experts believe that despite their innovation, their lack of collaboration led to this near-downfall. iTunes, iPod, iPad — these all require working with many developers, and is a big part of why they came back.

Microsoft started off as very open to collaboration and innovation from outside of the company, but that is not the case now. In order to get back into the groove, they have partnered with Nokia to enter the mobile phone market.

Collaboration can create commercial success, innovation, synergies, and efficiencies.

What change?

The amount of information generated now is vastly more than has ever been collected in the past. It is beyond our imagination.

How has library work changed? We still manage collections and access to information, but the way we do so has evolved with the ways information is delivered. We have had to increase our negotiation skills as every transaction is uniquely based on our customer profile. We have also needed to reorganize our structures and workflows to meet changing needs of our institutions and the information environment.

Deloitte identified ten key challenges faced by higher education: funding (public, endowment, and tuition), rivalry (competing globally for the best students), setting priorities (appropriate use of resources), technology (infrastructure & training), infrastructure (classroom design, offices), links to outcomes (graduation to employment), attracting talent (and retaining them), sustainability (practicing what we preach), widening access (MOOC, open access), and regulation (under increasing pressure to show how public funding is being used, but also maintaining student data privacy).

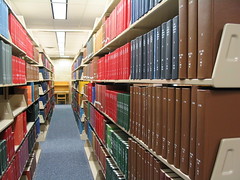

Libraries say they have too much stuff on shelves, more of it is available electronically, and it keeps coming. Do we really need to keep both print and digital when there is a growing pressure on space for users?

The British Library Document Supply Centre plays an essential role in delivering physical content on demand, but the demand is falling as more information is available online. And, their IT infrastructure needs modernization.

These concerns sparked conversations that created UK Research Reserve, and the evaluation of print journal usage. Users prefer print for in-depth reading, and HSS still have a high usage of print materials compared to the sciences. At least, that was the case 5-6 years ago when UKRR was created.

Ithaka S+R, JISC, and RLUK sent out a survey to faculty about print journal use, and they found that this is still fairly true. They also discovered that even those who are comfortable with electronic journal collections, they would not be happy to see print collections discarded. There was clearly a demand that some library, if not their own, maintain a collection of hard copies of journals. Libraries don’t have to keep them, but SOMEONE has to.

It is hard to predict research needs in the future, so it is important to preserve content for that future demand, and make sure that you still own it.

UKRR’s initial objectives were to de-duplicate low-use journals and allow their members to release space and realize savings/efficiency, and to preserve research material and provide access for researchers. They also want to achieve cultural change — librarians/academics don’t like to throw away things.

So far, they have examined 60,700 holdings, and of that, only 16% has been retained. They intend to keep at least 3 copies among the membership, so there was a significant amount of overlap in holdings across all of the schools.